Indexing & Abstracting

Full Text

Research ArticleDOI Number : 10.36811/ijpmh.2019.110002Article Views : 4803Article Downloads : 41

Creation of an out of hours child and Adolescent Mental Health emergency service

Anne-Frederique Naviaux1* and Nicolas Zdanowicz2

1Consultant Psychiatrist & Consultant Child Psychiatrist Health Service Executive (HSE) Summerhill, Community Mental Health Centre, Wexford, Ireland

2Consultant Psychiatrist, Head of Service Medecine Faculty, Université Catholique de Louvain Psychopathology and Psychosomatic Unit, Mont-Godinne University Hospital, Belgium

*Corresponding author: Anne-Frederique Naviaux, Consultant Psychiatrist & Consultant Child Psychiatrist Health Service Executive (HSE) Summerhill, Community Mental Health Centre, Wexford, Ireland, Tel: +353 (0) 53 9123899; Fax: +353 (0) 53 9155900; Email: annefrederique.naviaux@hse.ie

Article Information

Aritcle Type: Research Article

Citation: Anne-Frederique N, Nicolas Z. 2019. Creation of an out of hours child and Adolescent Mental Health emergency service. Int J Psychiatr Ment Health. 1: 13-19.

Copyright:This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Copyright © 2019; Anne-Frederique N

Publication history:

Received date: 28 January, 2019Accepted date: 06 February, 2019

Published date: 08 February, 2019

Abstract: Both Wexford and Waterford Counties are badly suffering from the lack of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). This is directly connected to the lack of CAMHS consultants to lead these services. Accessing the existing CAMHS services, especially in emergency, is particularly difficult as the waiting lists are ever growing, and therefore delaying the possibility of an early first appointment. An emergency “out of hours” child psychiatric service has been developed, in order to provide help when the CAMHS services are not accessible. Providing a service for under 18 years old patients with mental health issues presenting in Accident and Emergency (A&E) or hospitalised on a Ward (Paediatric, psychiatric or other) and also sometimes “off-site”, it functions with extremely limited resources (a consultant psychiatrist and a doctor in psychiatric training), and therefore needs an efficient triage procedure. The triage tool that was chosen is the Irish Child Triage System (ICTS) that was launched in Ireland by the RCSI in 2016. It operates in Wexford General Hospital (WGH) and in University Hospital Waterford (UHW). Between February and August 2018, every intervention provided by the Consultant Psychiatrist responsible for this “emergency out of hours” service was recorded; this includes interventions on both sites (WGH and UHW), In A&E but also on the Wards (Pediatric, Psychiatric, Medical and Surgical), both face to face consultations with the Consultant but also phone supervisions provided by the Consultant to the Doctor in psychiatric training on call for Psychiatry (UHW). The purpose of this article is to review the first figures of attendance of this new service provided and to discuss its profitability. Within 7 months, a total of 675 interventions was provided by the Consultant Psychiatrist on call for this new out of hours CAMHS service.

Keywords: Child and Adolescent Psychiatry- Emergency Department– Out of hours - Ireland- Triage- out of hours- Irish Children Triage System (ICTS)

Introduction

Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) are required more than ever in Ireland. At the same time, in a context of poor resources (mainly due to the lack of consultants to lead these services), accessing the existing CAMHS teams is problematic, especially in emergency, and the demand keeps and will keep increasing. Indeed, Ireland has an increasing young population: the total population aged less than 18 years increased by 10.9% between 2006 and 2011. This increase was particularly large in 2 age groups: the 0-4years and the 5-12 years age groups. (1) Currently, 25% of the Irish population is under 18 years of age [1].

With such a young population, Ireland also has an increasing need for Youth Mental Health Services: For the past decades, we have observed an increasing demand for Child and Adolescent mental Health Services [2,3] and an increase over time in the prevalence of mental illness in young people (HSE, Fifth Annual report of Child and Adolescent Mental Health services, 2014). The World Health Organization [4] predicts that childhood neuropsychiatric diseases will be one of the causes of mortality and disability among the five most common diseases of adolescence in 2020. In such a context, in both Wexford and Waterford Counties, we decided to be creative and to develop a new type of service: an out of hours Emergency Mental Health Service for Young People.

A vision for change

In Ireland, “A Vision for Change” (AVFC) [5] is a strategy document which sets out the direction for Mental Health Services (which includes CAMHS). It describes a framework for building and fostering positive mental health across the entire community and for providing accessible, community-based, specialist services for people with mental illness. This policy was developed by an expert group, which combined the expertise of different professional disciplines, health service managers, researchers, representatives of voluntary organisations, and service user groups. To put it in a nutshell, AVFC describes and recommends an ideal way to staff, organize, deliver and develop CAMHS… For example, AVFC [4,5] recommends the following CAMHS services per 300 000 total population:

- A total of 7 multidisciplinary community mental health teams (MHTs) which includes: 2 teams per 100 000 population (1/50,000) +1 additional team to provide a hospital liaison service per 300 000 population+1 day hospital service per 300 000 population.

- Each multidisciplinary team (MDT), under the clinical direction of a consultant child psychiatrist, to have 11 whole-time equivalent (WTE) clinical staff and 2 WTE administrative staff.

- Each CAMHS team should comprise: 1 consultant psychiatrist, 1 doctor in training, 2 psychiatric nurses, 2 clinical psychologists, 2 social workers, 1 occupational therapist, 1 speech and language therapist, 1 childcare worker and 2 administrative staff.

A reality check

These AVFC recommendations for CAMHS, were created in a period of abundance (before the recession) and can’t be applied these days principally because of the lack of resources (especially regarding the lack of CAMHS Consultants) which would be required to provide such a model of care. For example, currently, only 2 out of 5 posts of CAMHS consultants are filled for the geographic area of both Wexford and Waterford Counties. Without clinical lead, these CAMHS struggle to provide a full service as expected and waiting lists gets longer. The number of patients waiting for their first appointment in CAMHS [3] is gradually increasing because of a high number of patients, long follow-up times, and insufficient number of physicians. Long waiting times decrease the rate of attendance at the first appointment and lead to waste of time for the team, delayed solution of problems, and inability to evaluate cases of top priority in time. Demonstration was made that psychopathology becomes actually more severe during long periods in many patients. This is particularly frustrating, knowing that a range of efficacious psychosocial and pharmacological treatments exists for many mental illnesses in children and adolescents, and knowing that long-term consequences of untreated childhood mental illness are costly, in both human and fiscal terms [6].

Presenting to emergency departments in hospital

But if these young patients cannot access (soon enough) CAMHS, they do present to Emergency Department (ED) in hospital, where they expect to be psychiatrically assessed, investigated, treated and linked in with the appropriate inpatient or outpatient services [2,7].

The idea: an out of hours camhs cover for waterford/wexford

During opening hours, these patients used to be seen from a psychiatric point of view by CAMHS in hospital, and out of hours, the emergency psychiatric cover was provided by the adult psychiatric team on call as there was no proper CAMHS on call. 2 extra factors contributed to the creation of the ‘out of hours’ CAMHS cover in Waterford/Wexford. On one side, from the 01.09.2016 onwards, the adult psychiatrists in UHW stopped providing an out of hours ‘cover’ for patients under 18 years. On the other side, from January 2017 onwards, the psychiatric care provided during opening hours by the CAMHS teams for children in WGH was ceased. Indeed, CAMHS being under resourced could not manage to deal appropriately with the always growing amounts of young patients presenting directly to hospital and stopped to provide that type of intervention. It is in this context that an ‘out of hour’ child psychiatry cover was initiated; it has been active since 01.09.2016, and has continually been adjusting as circumstances have always been changing (especially depending on how operational the regular/day CAMHS were). It has been operated by one consultant psychiatrist and the doctor in psychiatric training on call when the consultant’s presence was not necessary (usually consultant on WGH site and doctor in psychiatric training in UHW site).

Methods

In order to measure how useful this new service was, we agreed to record every single intervention provided by the Consultant Psychiatrist on call for this new service. There were basically 2 types of interventions: face to face consultations (where the Consultant Psychiatrist was directly meeting and assessing the patient and his/her family) and phone supervisions (where the Consultant Psychiatrist was clinically guiding and supervising the Doctor in training who had been directly meeting and assessing the patient and his/her family). In some situations, the phone supervision was followed by a face to face consultation provided by the Consultant on call. For each intervention, we recorded 8 parameters: the site on which the patient was presenting (WGH or UHW) and the date and time of the intervention, the gender of the patient, the age of the patient, the address of the patient, the reason the patient was presenting for a psychiatric assessment, if the patient was already linked in with local services and if there was a follow-up needed with the local services. In this article, we are going to specially investigate the amount and type of interventions provided.

A total 675 interventions in 7 months amongst 3 sites

Between February 2018 and August 2018, a total of 675 interventions were provided by the ‘out of hours’ CAMHS Consultant between both hospitals (including off site consultations). Off-site consultations were provided in the situations that required a young person to be psychiatrically assessed in emergency while the patient was not in hospital. These were systematically provided by the Consultant (home visit, school intervention, GP or primary care settings…). The triage tool used on all sites was the Irish Child Triage System (ICTS) (Table 1).

| Table 1: Consultant Intervention per type, site and month. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 2018 | March 2018 | April 2018 | May 2018 | June 2018 | July 2018 | August 2018 | TOTAL | |

| Patients seen by ‘out of hours’ CAMHS Consultant Psychiatrist In WGH | 12 | 29 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 59 | 54 | 231 |

| Phone Consultations by ‘out of hours’ CAMHS Consultant Psychiatrist In WGH | 21 | 27 | 18 | 21 | 23 | 60 | 62 | 232 |

| Patients seen by ‘out of hours’ CAMHS Consultant Psychiatrist In UHW | 0 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 23 |

| Phone Consultations by ‘out of hours’ CAMHS Consultant Psychiatrist In UHW | 2 | 21 | 20 | 27 | 36 | 35 | 27 | 168 |

| Off Site Consultations by ‘out of hours’ CAMHS Consultant Psychiatrist | 1 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 21 |

| TOTAL Patients Seen by ‘out of hours’ CAMHS Consultant Psychiatrist | 13 | 39 | 42 | 32 | 27 | 64 | 58 | 275 |

| TOTAL Phone Consultations/supervisions by ‘out of hours’ Consultant Psychiatrist | 23 | 48 | 38 | 48 | 59 | 95 | 89 | 400 |

| TOTAL | 36 | 87 | 80 | 80 | 86 | 159 | 147 | 675 |

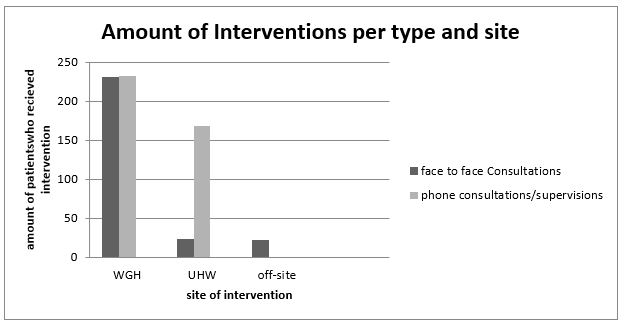

Comparison of intervention type

Basically, we are having a look at the interventions that required the Consultant Psychiatrist to assess face to face the patient and his/her family, versus the phone interventions. During these 7 months, the Consultant psychiatrist of this new out of hours service personally assessed a total of 275 patients (231 patients in WGH, 23 in UHW and 21 off-site) and provided 400 phone consultations/supervisions (232 in WGH and 168 for UHW). This means that the majority of the amount of interventions provided by the Consultant Psychiatrist of this new out of hours CAMHS were predominantly made by phone (59%) rather than face to face (41%). This also means that the vast majority of the interventions were provided in WGH (463), followed by UHW (191) and off-site (22) (Table 2,3).

| Table 2: Comparison of the types of intervention (phone vs face to face consultations. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Site of intervention | Phone Consultations/ Supervisions | Face to face Consultations | Total amount of Interventions |

| WGH | 232 | 231 | 463 |

| UHW | 168 | 23 | 191 |

| Off Site | 0 | 21 | 21 |

| All sites together | 400 | 275 | 675 |

| All site together (%) | 59% | 41% | 100% |

| Table 3: Comparison of the amounts of Interventions per site. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions | WGH | Off Site | UHW | Total amount of Consultations (per type) |

| Face to face Consultations | 231 | 21 | 23 | 275 |

| Phone Supervisions/ Consultations | 232 | 0 | 168 | 400 |

| Total of Interventions(per site) | 463 | 21 | 191 | 675 |

| Total of interventions (%)(per site) | 69% | 3% | 28% | 100% |

Comparison of interventions depending on site and type

The interventions were provided for patients seen either in WGH, UHW and off-site. In WGH:231 patients were seen face to face by the Consultant Psychiatrist, while phone consultations were provided on 232 occasions; which shows an equal amount of both types of interventions on that site (on which the out of hours CAMHS Consultant works alone or teaming with different hospital services, especially Paediatrics but with no doctor in psychiatric training on site).

In UHW: 23 patients were seen face to face by the Consultant Psychiatrist, while phone supervisions were provided on 168 occasions. This might be easily explained by the fact that as there is a doctor in psychiatric training on site, all patients are initially seen by him and were provided for with phone supervision. In only 23 cases, the out of hours CAMHS Consultant Psychiatrist had to assess these patients face to face. As mentioned earlier, all interventions off-site were face to face consultations provided by the out of hours CAMHS Consultant Psychiatrist (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Amount of interventions per site and type.

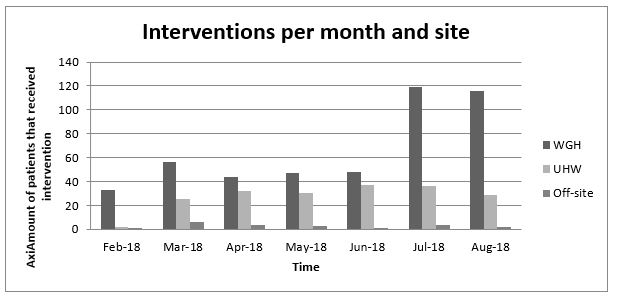

Comparison of interventions per month and site

The amount of interventions is also varying according to the time of the year, and especially if the young people are in school or not. Indeed, during school holidays, the amount of young people requiring out of hours CAMHS services is much more important than during the rest of the year. Another factor that might also explain the increase in the service interventions is the fact that once people became aware of its existence, they were more of them to request its provision (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Interventions per month and site.

Special considerations

It is important to highlight how the Paediatric services in both hospitals, but especially in WGH, have been extremely cooperative and understanding; accepting to admit and care for children with psychiatric needs when no CAMHS bed was available, and facilitating the psychiatric follow up on the Wards by the out of hours CAMHS cover. In the same way, the Department of Psychiatry (Adult Psychiatric Ward) in UHW agreed to admit on multiple occasions some children with mental health issues who needed, but could not avail from a CAMHS bed, and were not suitable for a paediatric Ward.

Discussion

With this high amount of intervention (675 in 7 months, so about 3 to 4 patients’ interventions per night), the service is a success. Thanks to its creation, and despite the lack of CAMHS services, continuity of care has been attempted and achieved. Of course, some improvements are needed, and we are dedicated to work in that direction. We are already working on a new tool; a post triage tool specific to Mental Health of young people. Developing a practical though detailed post-triage mental health tool for young patients, like it has recently been developed for an adult population (review in December 2020), could also help to a full safe and efficient provision of care.

Availing from a dedicated and specially organised place within the A&E department and/or on the Wards, to meet young patients presenting either with a psychiatric emergency or in crisis, and their family, is certainly crucial. Making this environment safe for both patients and staff is also essential. Providing observation or short hospitalisation beds in this system could help for the assessment /monitoring of some patients and also help to diffuse crises and avoid inappropriate referrals to an already saturated CAMHS system. In order to make this psychiatric emergency/crisis intervention centre functional, we believe that not only psychiatrists should be present 24/7, but that psychiatric nurses and social workers should also be present 24/7.

References

- Barry A. 2017. Children’s lives ‘at risk’ over lack of nationwide out-of-hours mental health services. [Ref.]

- Wallis M, Azam M, Akhtar F. 2017. Paediatric Admissions due to perceived mental health and behavioural issues: audit 2017, Wexford General Hospital Audit 2017 report [Ref.]

- Aras S, Varol Tas F, Baycara B. 2014. Triage of Patients in the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Outpatient Clinic. Archives of Neuropsychiatry. 51: 248-252.[Ref.]

- HSE RCSI. 2015. A National model of Care for Paediatric Healthcare Services in Ireland Chapter 13: CAMHS.Health Service Executive, Ireland. [Ref.]

- HSE. 2006. A vision for change, 2006, Health Service Executive (HSE) Ireland[Ref.]

- HSE. 2016. Irish Children’s Triage System (ICTS) # Children’s Ireland, 2016 Triage, June2016, Health Executive Service (HSE).[Ref.]

- Goldstein A, Findling R. 2006. Assessment and Evaluation of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Emergencies. Psychiatric Times. 23: 9. [Ref.]

- Naviaux AF. 2018. Triage of Children with Mental Health Difficulties Presenting in A&E in a General Hospital, Psychiatria Danubina. 422-425. [Ref.]

- College of Psychiatrists of Ireland (review date 2020): Post Triage Mental Health Triage Tool, National Clinical Programme for Emergency Medicine l, version 1, December. 2017. [Ref.]

- Dolan M, Fein J. 2011. Pediatric and Adolescent Mental Health Emergencies in the Emergency Medical Services System. Pediatrics. 127: 5. [Ref.]

- Gerson R, Havens J. 2015. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Emergency: A public Health Challenge Psychiatric Times. 32: 11. [Ref.]